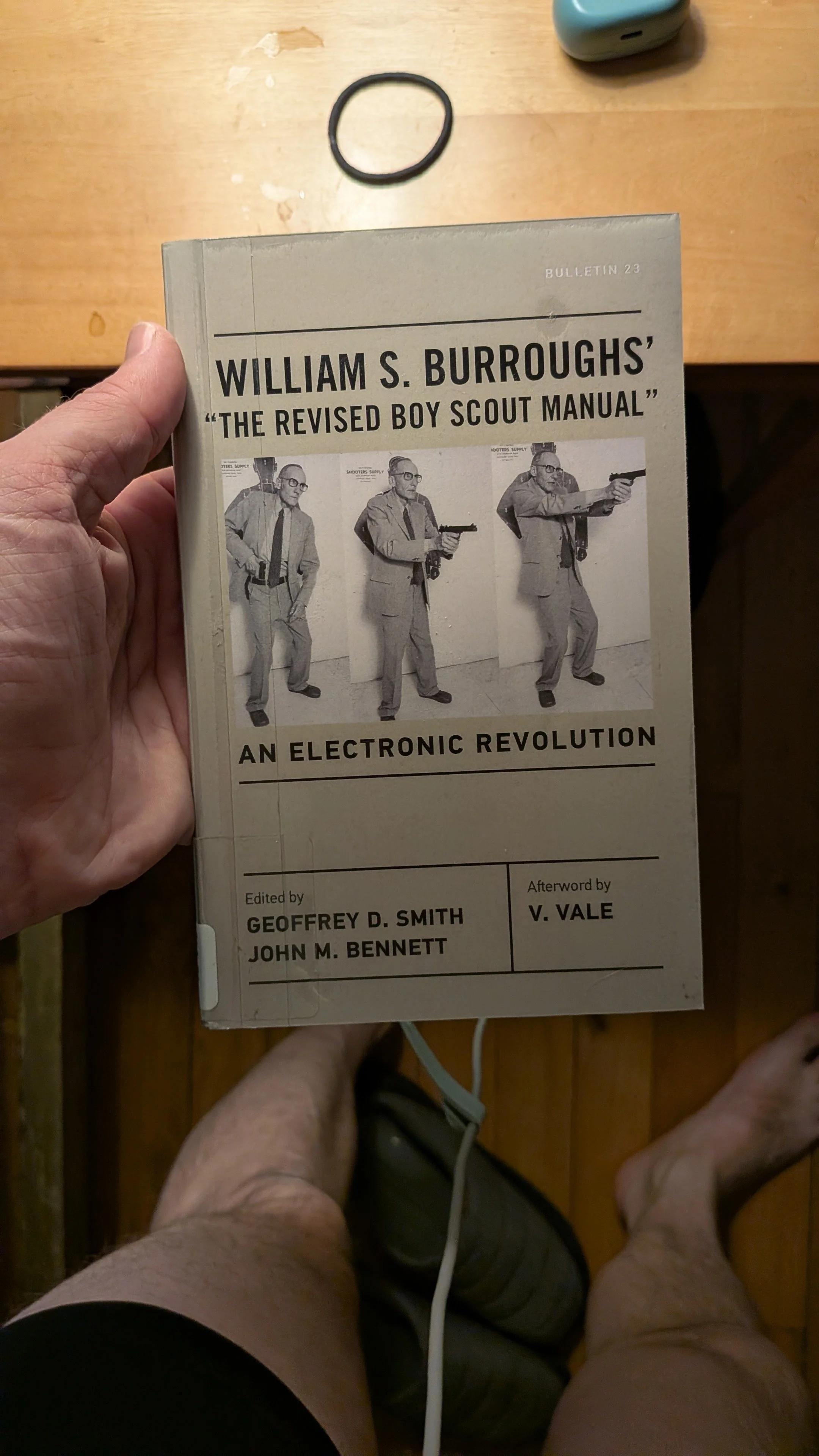

THE REVISED BOY-SCOUT MANUAL - WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS

I live in Lawrence, which, among other things, is famous for being the place where Burroughs lived longest. For the last 17 years of his life. True, it is the least celebrated of his homes, he didn’t kill anyone in a drunken game here, he didn’t write any major work here, it’s not where he influenced the early punk scene. It’s no Beat hotel. But, despite how gnarly so much of his work is, the town has quasi-embraced him, there is a nice little trail by the creek that is named after him. Also, you would think this would mean that the second most famous writer associated with the city (Langston Hughes being the first, tho, in a sort of reverse way in that he spent his early life here and never returned) would have more of his books available at the library. They do not. But, they do carry this volume, which is one of the more obscure, late-period Burroughs work and the only one I hadn’t read from their collection so I grabbed it and checked it off of my read-all-the-Burroughs quest (I’m getting close, but there are a lot of obscure, hard to find volumes). I would not say this one is essential. It’s a sort of distilled and less literary version of his major themes. It is a manuel in that it’s didactic and instructional. It’s about Burrough’s major theme, resisting control. As always, it goes from base-level control, as in drug addiction, to governmental/cultural control, up to esoteric or religious control (like the Nova Mob, or Mayan calendar control, or the One God Universe or any number of Burroughs obsessions or names for what is basically the same thing). To him, it’s all the same, and we can resist them in the same ways, namely, by scrambling up the scripts, through cut-up techniques. He mentions using tape recorders all the time and mixing up the tapes and playing them back, or overlaying something like the call to prayer over the sound of pigs or other transgressive acts meant to short-circuit the scripts that are running the world. He also suggests acts of assassination against the 10% of the world that runs the show (which actually lines up with the 5% ideology; if only Burroughs had met the Wu-Tang Clan) but decentered, as sort of leaderless resistance. It’s interesting how much he was correct, but in sort of a reversed way, in that the systems he was trying to combat actually adapted these techniques. Nothing says cut-up like scrolling a social media site, or trying to read the news. Music is quite sample based, people can’t even watch movies any more, their attention spans is so shot. Everything is pastiche and jumps moment to moment. So Burroughs was right about that. What he was wrong about was what the effect of this stuff would be. Instead of liberation and a breakdown of control, these techniques have alienated us from one another and driven us insane. The ability to swipe through dog videos and drone footage and rage-bait and family news destabilizes but also traumatizes and trauma leads to a desire for safety and more control. Likewise, this type of low-level warfare that Burroughs is describing is also de rigueur these days. Assassinations, sabotage, decentered resistance, psyops, terrorism, drugs as weapons, all of this is much more effectively deployed by forces of control than by any resistance force. Seems bad to live in a world more depressing than the one Burroughs foresaw, but here we are. Anyway, this is easily the most straightforward presentation of Burrough’s ideas. I prefer the novels, which covers this material but in a more artistic manner, you get his super-bugged out (pun intended) flights of fancy, but this is a pretty good distillation of his obsessions and theories.